Los vikingos en Irlanda » Historia

Los vikingos en Irlanda

Autor: Emma Groeneveld

En los comienzos de la Europa medieval, uno de los principales protagonistas de las aterradoras historias hechas realidad eran los famosos Vikingos merodeadores y saqueadores, que se desbordaban de sus naves cabeza de dragón en un estado de sed de sangre, sedientos de oro. Con su amenazadora presencia que eventualmente se extendía desde el este de Europa y el Mediterráneo hasta América del Norte, ninguna tierra parecía segura, y fue temprano en su ejercicio de trotamundos que los vikingos zonificaron en las atractivas costas verdes de Irlanda. A partir del 795 CE en adelante, los monasterios y las ciudades fueron saqueados o destruidos en persistentes incursiones, seguidas por la construcción de fuertes y asentamientos que permitieron a estos escandinavos convertirse en jugadores comodín en la escena política irlandesa. Los vikingos, aunque perdieron su poder autónomo entre finales del siglo X y principios del siglo XI, ya se habían integrado a la sociedad irlandesa a través del matrimonio mixto y el contacto cercano con los lugareños, y dejaron una huella duradera tanto en el comercio como en la cultura.

Ataque vikingo

EL EMPATE

Sin embargo, lo que motivó exactamente a los vikingos a zarpar hacia Irlanda (o las Islas Británicas en general) está sujeto a un debate continuo. En el oeste de Noruega, donde la tierra que no intentó matarte o tus cultivos era un poco escasa, la búsqueda de nuevas tierras puede haber sido un pequeño factor de presión. Esto parece encajar con los vikingos noruegos que golpean a sus compañeros escandinavos al golpe en la expansión hacia el oeste, alcanzando las Orcadas en el siglo VII EC. Fueron los nórdicos los que terminaron en las costas irlandesas.Cuando, a partir de finales del siglo VII EC, el aumento de los contactos comerciales con Europa occidental trajo a los escandinavos susurros de riqueza en Europa, así como historias del conflicto interno de los reinos, un factor de atracción presentado pulcramente en bandeja de plata. Además, los escandinavos adquirieron el conocimiento técnico de las velas, algo que originalmente les faltaba, también de Europa occidental, lo que les permitió remodelar sus tímidas embarcaciones para convertirlas en buques rápidos y letales. Solo así, todos los ingredientes de una expedición de ataque exitosa estaban allí.

LAS RAIDS TEMPRANAS (795-837 CE)

Los anales medievales irlandeses, escritos por monjes y clérigos que se encontraban entre los testigos oculares, registran la primera incursión vikinga en 795 CE cuando la isla de Rathlin frente a la costa noreste del continente y el gran monasterio de San Columba en la isla de Iona fue atacada por extraños. Habían salido de la nada, entrando y saliendo y llevándose sus tesoros en expediciones bastante descoordinadas creadas por bandas de guerra independientes. En los años que siguieron, los vikingos llevaron sus barcos al mar de Irlanda, por ejemplo, quemaron la isla de San Patricio justo al norte de Dublín en 798 CE. Estos esfuerzos iniciales fueron llevados a cabo por no más de dos o tres naves a la vez, apenas flotas apiladas con innumerables hombres del norte, en una carrera de atropello y fuga.EN LOS PRIMEROS 40 AÑOS DE INCURSIONES, LOS VIKINGOS PERMANECERON COMO WRAITHS FALSOS, ASESINANDO LAS REGIONES COSTERAS IRLANDESAS Y DESTRUYENDO MUCHOS CENTROS MONÁSTICOS.

En 807 EC, los vikingos también se habían desplazado a las bahías occidentales, y la mayoría de los objetivos que escogieron -monasterios y pueblos pequeños- eran presas fáciles; tenían los elementos de sorpresa y velocidad y generalmente permanecían dentro de los 30 km de agua navegable, lo que los mantenía altamente móviles. A pesar de algunas instancias de resistencia local exitosa, los irlandeses probablemente tenían una flota subdesarrollada, sin fuertes costeros y unos poco prácticos 480 km de costa para defender; un poco de un trabajo sin esperanza. El atractivo de los monasterios era obvio: no solo albergaban monjes, sino que también se fabricaban finas piezas de metal para adornar libros sagrados y relicarios, y el tesoro almacenado también era abundante, lo que facilitaba el transporte del botín. La comunidad de Iona se conmovió tanto después de ser saqueada en 795 CE, incendiada en 802 EC, y ver a 68 de su comunidad destrozados por hachas vikingas en 806 CE que en realidad volvieron a albergar sus tesoros y parte de su personal a un nuevo monasterio construido tierra adentro en Kells.

Comprensiblemente molesto por toda esta situación, la persona que anota el récord en los Anales irlandeses del Ulster(nuestra fuente principal en las incursiones vikingas, están fuera por un año en sus cuentas, pero aquí se hace referencia de manera corregida) para el año 820 CE se queja de que en ese momento:

El mar arrojó inundaciones de extranjeros sobre Erin, de modo que no se pudo encontrar un refugio, un lugar de aterrizaje, una fortaleza, ningún castillo, sino que fue sumergido por olas de vikingos y piratas. (820)En los primeros 40 años que los incursores tocaron puertas irlandesas, los vikingos siguieron siendo espectros sin rostro, hostigando a las regiones costeras irlandesas en su mayoría en la mitad norte de Irlanda y saqueando muchos centros monásticos. Antes del 837 dC, no aparecen nombres vikingos en ninguno de los registros irlandeses, y no es hasta mediados del siglo IX cuando comienzan a aparecer los reyes vikingos; esta fase temprana de redadas fue solo un preludio.

Iglesia de San Kevin, Glendalough

AUMENTAR LA PRESIÓN Y EL ACUERDO (837 CE EN ADELANTE)

Las incursiones tempranas habían dejado claro el potencial de Irlanda para los ojos hambrientos de tesoros, y desde la década de 830 CE los grupos vikingos escalaron la presión, los anales irlandeses enumeraban alrededor de 50 ataques específicos contra monasterios y nueve grandes ataques contra iglesias y personas en lugares como Leinster y las tierras de Uí Néill entre c. 830 y 845 CE. No solo se robaron objetos de valor; tomar cautivos y cobrar el rescate también era una buena forma de ganar algo de dinero.Una nueva fase en la participación de los Vikings con Irlanda es identificable desde 837 CE. Siguiendo la creciente escala de redadas, en este año una flota de vikingos mucho más gigantesca navegó por los ríos Liffey y Boyne hacia los territorios del interior, atacando las tierras de Brega en el sur del condado de Meath:

Una fuerza naval de los Norsemen sesenta naves fuertes estaba en el Bóinn, y otra de sesenta naves en el río Life. Esas dos fuerzas saquearon la llanura de la vida y la llanura de Brega, incluidas las iglesias, los fuertes y las viviendas. Los hombres de Brega derrotaron a los extranjeros en Deoninne en Mugdorna de Brega, y seis de los escandinavos cayeron. ( Los anales de Ulster, 837. 3)Estas naves, probablemente navegando desde las áreas ocupadas por vikingos en Escocia, parecen haber transportado alrededor de 3.000 hombres sanos en total, quienes por primera vez se tomaron la cabeza contra la resistencia local apropiada, un tema que se llevó a cabo como una fuerza del sur. Uí Néills también se enfrentó a los vikingos, aunque con menos éxito que "un número incontable fue masacrado" ( Annals of Ulster, 837. 4). Empujando hacia arriba las vías navegables de la región central del este, donde pronto se convirtieron en lugares habituales, en vez de sus antiguos pinchazos a lo largo de las costas, los vikingos ahora parecen haber sido organizados en expediciones reales procedentes de Viking Escocia, con jefes o reyes vinculados juntos varios grupos y derrochando recursos para apoyar estas misiones. Con este nuevo enfoque interior, las fortalezas, las granjas y las ciudades también se vieron cada vez más amenazadas. En general, desde 837 CE en adelante, los objetivos más grandes (como las ciudades monásticas más grandes Armagh, Glendalough, Kildare, Slane, Clonard, Clonmacnoise y Lismore) fueron golpeados por fuerzas más grandes que en los primeros días, mientras que las iglesias locales más pequeñas donde había menos de ser saqueado puede haber escapado de la embestida.

Las grandes expediciones trajeron mayores recompensas, y aunque los artefactos religiosos que los nórdicos saqueaban generalmente no tenían el valor metálico más alto, el hecho de que llevaran significado al irlandés cristiano significaba que podían ser rescatados. La toma de esclavos, inusual para los irlandeses locales, también era una característica habitual de las incursiones vikingas en general y ayudaba a llenar la caja.

Los vikingos en Dublín, 841 d. C.

Desafortunadamente para los irlandeses, en lugar del frío invernal que interrumpía las temporadas de incursiones vikingas y les daba un poco de tiempo para respirar, desde al menos 840 EC en adelante, los nórdicos comenzaron a invernar en Irlanda. Se refugiaron en Lough Neagh en ese año y establecieron las primeras fortalezas costeras que también albergaban sus barcos, conocidos como longphorts, en al menos 841 CE, incluyendo uno en Dublín. Como señalan los analistas, en 841 CE "Hubo un campo naval [ longphort ] en Duiblinn..." (841. 4), y luego, con sorpresa casi palpable, la entrada del 842 CE dice "Los paganos todavía en Duiblinn" (842). 2). Las incursiones ahora podrían ser lanzadas sobre objetivos desprevenidos en pleno invierno, con esclavos prisioneros en los nuevos cuarteles de invierno de los vikingos.Los longphorts de los vikingos se convirtieron en sus puntos de apoyo estratégicos como escalones para aumentar las actividades de saqueo a lo largo de la costa irlandesa, y prefiguró su asentamiento a más largo plazo en lugares como Wicklow, Waterford, Wexford, Cork, Limerick y Dublín, donde gradualmente incorporó el área circundante a los reinos costeros que competían con los otros irlandeses y nórdicos a su alrededor. En contraste con la situación en Inglaterra y Escocia, sin embargo, los escandinavos nunca ganaron ningún territorio irlandés sustancial.LA ANTIGUA PRESENCIA DINÁMICA DE LOS VIKINGOS HABÍA CAMBIADO AL LLEGAR A SER PACIENTES SEDENTARIOS EN SUS LARGOS TRAPOSOS, HACIENDOLOS MÁS VULNERABLES A LA RESISTENCIA IRLANDESA ATADO.

RESISTENCIA Y CONVERGENCIA

Estos nuevos desarrollos tuvieron unos pocos efectos colaterales. La amenaza de los vikingos ya no podía ser ignorada, ni siquiera por los reyes irlandeses que tanto amaban golpearse el uno al otro y pelear entre ellos, y en 845 CE Niall Caille, rey de Tara, descubrió que era muy capaz de infligir una derrota un grupo de vikingos en Donegal. Muchos éxitos militares irlandeses, como el de Maél Sechnaill I (a descendant of the southern Uí Néill dynasty who styled himself High King of Ireland) in 848 CE in which 700 Vikings allegedly bit the dust, followed. The Vikings’ formerly dynamic presence had shifted to them becoming somewhat sedentary ducks in their longphorts, making them more vulnerable to this stiffened Irish resistance.Besides antagonising the locals, the Vikings’ settlement actually also drew them into the Irish political scene, as Donnchadh Ó Corráin explains:

The Irish kings now made war on them [the Norse], now used them as allies and mercenaries in the shifting web of alliances at the centre of which lay the Uí Néill [an Irish dynasty] attempt to make themselves kings of Ireland. (Ó Corráin in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings, 89-90)With neither the Irish nor the Vikings being united, mixed groups of both could be found opposite each other. These alliances started going hand in hand with intermarriage at the very tops of these groups’ social hierarchies, drawing the Vikings ever closer into Irish society as a whole, and, by the second half of the 9th century CE, the Viking presence had become a familiar sight in Ireland. Tribute exacted from the lands they controlled and trade they conducted with the Irish also led the Vikings to build up commercial ties with their hosts.

Map of Ireland c. 950 CE

However, the Norse Vikings, busy trying to milk a stubborn Ireland to the best of their abilities, did not remain unchallenged. After decades of being the only magpies around, in 849 CE a Danish fleet came to check up on them and sailed into Irish waters. The Annals of Ulster record that:A naval expedition of seven score ships of adherents of the king of the foreigners (righ Gall) came to exact obedience from the foreigners who were in Ireland before them, and afterwards they caused confusion in the whole country. (849)The Danes clearly had the Norse – and not the Irish – as their target; in 851 CE they attacked both Viking Dublin and the longphort at Linn Duachaill, and defeated the Norse after a three-day long naval battle at Carlingford Lough in 853 CE, after which the Norse bounced back and finally drove the Danes off. With the Norse and the Danish as rival Viking groups, according to Dáibhí Ó Cróinín (250-251), it is not impossible that the Irish had initiated an alliance with the Danes and then sat back to watch things unfold.

By the end of the 9th century CE it had become clear to the Norse that Ireland would not part with its riches or its land as (relatively) easily as some of the other Viking territories like the ones in Frankia and England. Beyond their handful of settlements and their involvement in Irish society, the Viking presence could not stretch its wings much further and kept getting caught in Irish resistance. This may have pushed them to seek easier pickings in Iceland and the northwest of England, which reduced some of the pressure on Ireland.

VIKING DUBLIN

Viking Dublin, which had begun as a longphort in 841 CE and was taken over by a branch of Scottish Vikings led by Amlaíb (or Olaf) who teamed up with another Viking leader, Ímar (or Ivarr), in around 853 CE, probably suffered from similar difficulties. These two had transformed Dublin and the Irish Sea into the hub of Norse activity ranging from Scotland and England to the Isle of Man. For over 20 years their names are found time and again in the annals due to them wreaking havoc across the country and getting stuck into the northern Irish Sea region’s politics. However, after Ímar’s death in 873 CE, the records go quiet in terms of heavy-duty Viking activity in Ireland and it becomes hard to trace the doings of the Dublin kingdom’s dynasty, who might have become internally divided at this time.

Brian Boru

In 902 CE we are illuminated once more, though; what was left of the Dublin Vikings were driven out of town by the combined forces of Brega and Leinster:The heathens were driven from Ireland, i.e. from the fortress of Áth Cliath [Dublin]…and they abandoned a good number of their ships and escaped half dead after they had been wounded and broken. ( The Annals of Ulster, 902. 2)With Dublin now in Irish hands, it seems loads of Vikings upped and left Ireland and in more than a few cases camped out in England instead, for the time being.

After only a short break, in 914 CE the Waterford coast saw the sudden appearance on the horizon of a large amount of Viking sails, edging closer and closer, its human cargo reclaiming Waterford and ravaging the surrounding lands of Munster. Other bases such as Wexford, Cork, and Limerick were also hardhandedly returned to the Viking fold around this time, while Dublin was taken over by the original Dublin Viking group who also happened to rule York and Northumbria at this point in time. This overarching dynastic connection spurred on trade and urbanisation in the whole of Ireland as well as greatly boosting the resources of its single king, transforming Dublin into an economic and political centre from which the Irish kings also profited.

The Viking tale of Ireland finally takes its last turns around the end of the 10th century CE. It began with the Dublin Viking king Amlaíb Cuarán getting a bit overconfident, having conquest on his mind. After plunging his army’s swords into many Irish necks including that of the king of Leinster, he was promptly defeated in the kingdom of Meath in the battle of Tara, 980 CE in what the annalist calls "a red slaughter" (Brink & Price, 432). Mael Sechnaill mac Domnaill, king of Meath, then successfully steamrolled on towards Dublin, who in its surrender had to free all Uí Néill lands from tribute and free the Irish slaves within Viking territories. All of the Viking cities now came under either direct or indirect control of the Irish kings.

With the dragon-headed ship already pretty much sailed and the remaining Norse steadily integrating into the Irish political scene, the Battle of Clontarf fought in 1014 CE – despite its legendary status – simply reinforced this trend. Brian Boru, High King of Ireland encroached upon Dublin aided by Limerick Vikings, while the men of Leinster stood beside the Dublin Vikings in the typically mixed bag of alliances which had so come to characterise Irish politics in this period. The great melee that followed saw Brian Boru fall but Dublin lose, thus piling onto the earlier 980 CE defeat and snugly fitting Dublin as well as the other Viking cities further into the Irish political structure; they were now ruled by Irish overlords who saw them as "sources of income and power, not as the citadels of foreigners to be sacked" (Ó Cróinín, 267). The epilogue comes in the form of the Norman invasion of England in 1066 CE, whose descendants washed over Ireland from 1169 CE.

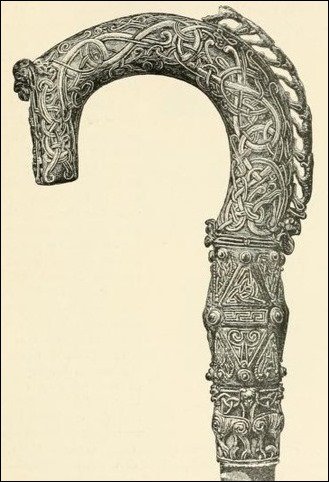

Clonmacnoise Crosier

IMPACT ON IRELAND & LEGACY

The picture of raiding Vikings unleashing their brutality and destruction upon Ireland seems clear from the early medieval accounts and, for good measure, tends to be etched in today’s minds. However, when looking closer at the context, one can only conclude that this is massively exaggerated. In terms of frequency, raids were not exactly a constant hazard during the early period, with only 25 monastic raids recorded between 795-829 CE while Ireland had a veritable sea of monasteries and churches in total. Even the ones that were hit more than once clearly bounced back fast enough to be hit again, and overall most monasteries survived this era.The damning judgement of bloodthirst attached to the Vikings stems from the hands of the very clerics who were in the first line of fire and obviously very upset at these ‘heathens’ or ‘pagans’ coming in and despoiling their sanctuaries. This hatred seeps through in their writings and gives an unfair impression of mass-scale destruction; rather than all "havens" being "submerged by waves of Vikings" ( The Annals of Ulster, 820), although probably traumatic, the raiding reality was a bit milder than that. Moreover, during the Viking period, the Irish themselves actually plundered more churches than the Norse did, and they would certainly not have needed any lessons in brutality from the Norse, being quite educated in that respect themselves already.

Although the territories the Vikings took were not very large and thus did not have a huge geographical impact on Ireland, the Vikings did end up significantly influencing Ireland in a political, economic, and cultural way. The Irish took over some Norse cues regarding warfare, especially regarding weapons and tactics, but it was the Viking longphorts grown into towns with commercial characters that gave Ireland, formerly lacking proper towns, a major, lasting boost. Furthermore, the extended Viking ties with the rest of the British Isles and continental Europe enlarged the Irish trading scene in general.

The progressing integration (reinforced by intermarriage) of the Viking kingdoms into Irish society especially throughout the 10th century CE not only saw Vikings embracing the same Christianity whose houses of worship they had initially come to attack but also saw Irish kings influenced by Viking ideas of kingship, which were more overarching. Finally, the most tangible impact to us can be seen in art and language: Scandinavian styles can be seen throughout Irish metalwork as well as the stone crosses of the time, and both names, as well as terms relating to typical Viking activities such as shipping, were loaned by the Irish, such as the splendid Old Norse knattar-barki (a small studded boat) becoming the Irish cnaturbarc.

The Viking’s exaggeratedly crazy reputation has ensured their survival in Europe’s collective memory, and despite being taken down a peg or two on contextual grounds their intricate relationship with Ireland is both fascinating and noteworthy.

Esta página se actualizó por última vez el 28 de septiembre de 2020

Contenidos Relacionados sobre Historia Antigua

LICENCIA:

Artículo basado en información obtenida del sitio web: Ancient History EncyclopediaEl contenido está disponible bajo licencia Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported. CC-BY-NC-SA License